Velocity Is Limited by the Path to the User

For engineers, maintainers, and teams who feel delivery friction more than coding friction.

Monday morning, two engineers on rotation open the pipeline and find a release blocked by a failed SBOM scan (software bill of materials). Was it a real vulnerability or just a scanner hiccup? Either way, the morning is gone before the deploy can move.

The Constraint Moved

Generation got cheap. Drafts and options are abundant. Verification and delivery stayed expensive. So velocity is limited by the path from merged code to a working install in a real environment.

- Generation is cheap. Drafts, prototypes, and options are abundant.

- Verification is expensive. Testing, integration, and safety still cost real time.

- The delivery path is binding. If you cannot get work into the world, you cannot learn from it. And if you cannot learn, you cannot compound.

By “distribution” I mean the delivery path: from merge to usable install. Not marketing. The literal path into the product.

The bottleneck is no longer creation. It is the delivery path: governance, packaging, and installs. This is not just regulated enterprise pain. For startups and non-regulated teams, the delivery path is onboarding, provisioning, upgrades, and “does it work in my environment.” That path is where velocity now stalls.

That SBOM failure is distribution drag in its pure form: nothing about the code changed, but progress stopped anyway.

I saw the same in open source. Users would wait days for a physical Waveshare dev board to ship, but drop off rather than run a quick Docker setup. That was the moment I realized my bottleneck was not the code. It was the path into the product.

Fewer Surfaces, Faster Learning

The good news: architecture, build pipeline, and packaging choices can make the delivery path dramatically simpler.

This is not about Rust versus Node. The rule: pick designs that reduce the number of delivery surfaces, make handoffs inspectable, and let you ship partial capability without shipping a new platform.

- Enterprise: monolithic agent → decomposed multi-agent workflow. In one case I’ve seen failure rates drop from roughly a third to effectively zero, latency from 40–100s to 10–20s, tool calls from a dozen to three. Smaller services isolate gated deploys and reduce blast radius.

- OSS: Node.js with hand-rolled UI → Rust core with event bus and adapters. Result: single binary for most environments, optional adapters when needed, far less packaging glue.

Flexible systems keep delivery paths open under pressure: composable parts, inspectable handoffs, and changes that do not collapse under new constraints.

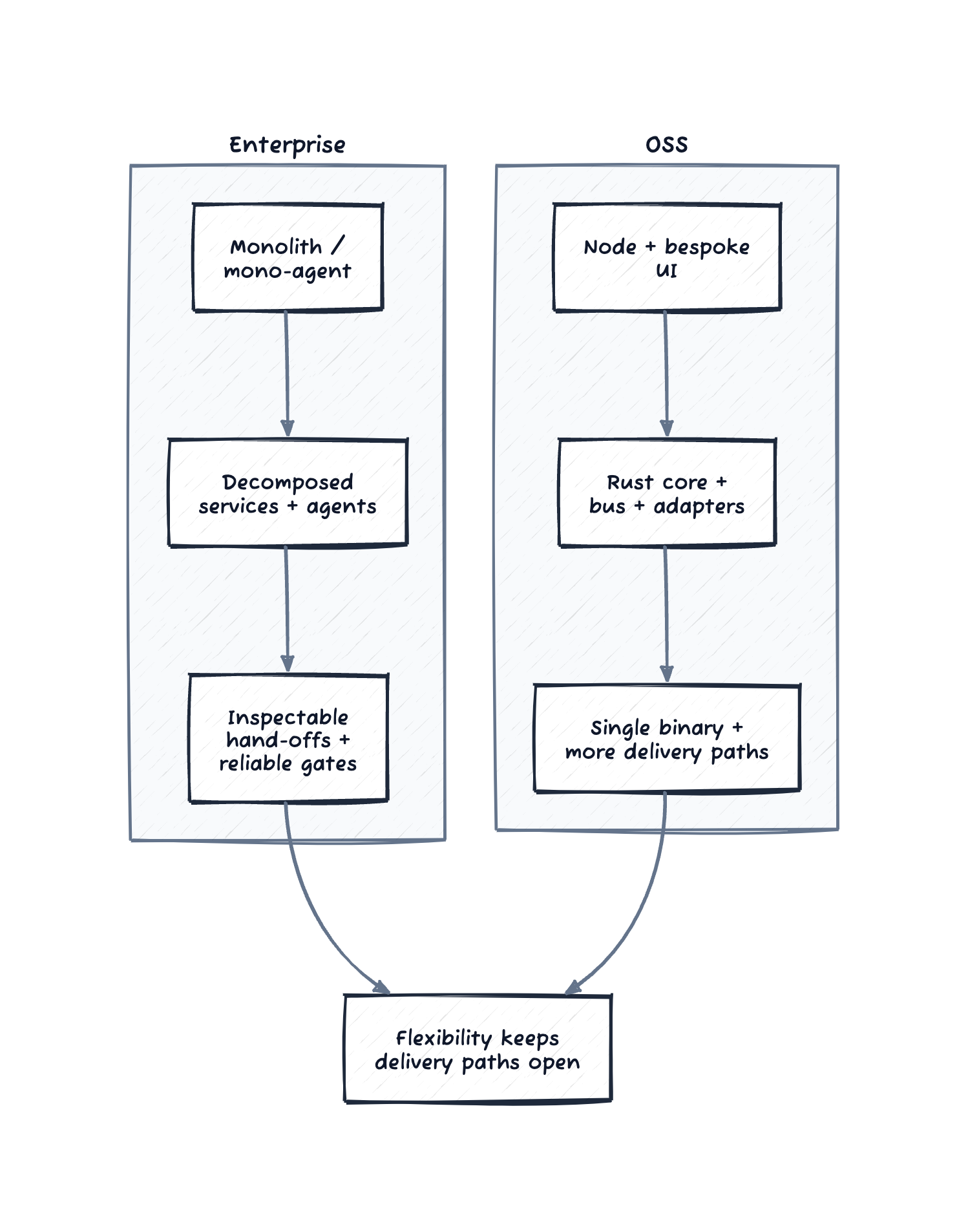

Figure: flexibility in enterprise and OSS keeps delivery paths open.

The examples that follow show what the pain looks like before these shifts—and the specific moves that helped.

The Enterprise Grind: Governance as the Silent Velocity Killer

In regulated environments like hospitals, compliance is non-negotiable. But how it is implemented often turns necessary checks into major roadblocks.

The dev teams I am helping operate with zero dedicated IT support, so engineers end up handling the full deployment pipeline themselves. Pushing one update through dev, staging, and prod takes 15+ minutes of close attention, multiple times a day. Each step hits manual approvals at CI and delivery gates, with devs clicking through lists one by one. Skip something and you start over.

The worst part is flaky security scans that fail unpredictably over weekends, often from temporary glitches like network hiccups or false alarms on dependencies. Monday rolls around, and the pair on shift finds a blocked deploy, then spends hours figuring it out: real issue, scanner error, or bad luck. Time slips away on fixes, throwing off plans and holding up important changes.

Governance is physics—you cannot wish it away in regulated environments. But brittle, manual governance is self-inflicted drag. The goal is reliable, low-touch governance.

The first moves I look for are always the same: reduce the number of clicks per deploy, add retries and clearer failure modes on scans, and make approvals explicit and consistent instead of tribal. Prefer gates that are deterministic, retryable, and explainable. GitOps-style deploys and scanners you can make deterministic in your environment help—but the principle matters more than the specific tools. That is not glamorous work, but it is where a large part of velocity lives.

The same trap shows up in open source. Just as OSS users balk at Docker setup, enterprise devs rage at scan flakes. Both are the system saying “no” in ways that feel arbitrary.

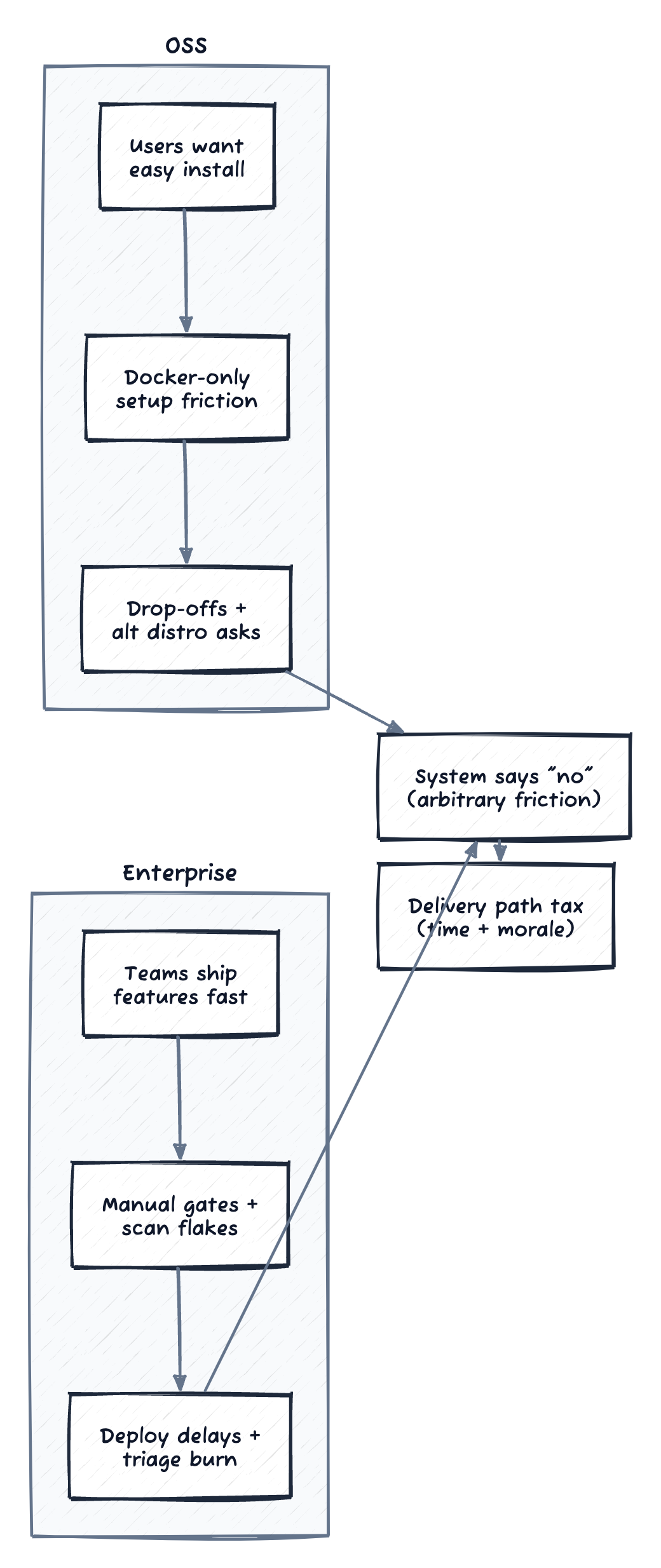

Figure: different sources of friction, same delivery-path tax.

Mirroring the Trap in Open Source: When “Easy Install” Matters More Than Features

This enterprise friction lines up with what I have seen in my open source projects, unified-hifi-control (a multi-protocol audio bridge) and roon-knob (a physical volume knob for Roon). It is the same arc you see when OSS projects move beyond Docker-only and add official packages or installers. As these picked up users, the early feedback was not about new features. It was “make it easy to install.”

I started with Docker-only, which felt straightforward as a solo maintainer. Users were not having it. Some were on NAS devices like Synology or QNAP, where Docker felt tacked on and unreliable. Others wanted tighter integration with systems like Roon or Logitech Media Server (LMS), preferring built-in plugins to container workarounds. The project supports a physical dev board that takes days to ship, but people would drop off rather than deal with a quick Docker setup.

My release pipeline made it worse. Compiling for different platforms (Linux targets, macOS universal, Windows), packing web assets, pushing Docker images, and building packages ran about 40 minutes each time. Users did not feel that delay directly, but it slowed my response. Adding a new option, like the Roon Extension Manager repo or sketching an LMS plugin, meant burning hours on reruns.

A focused pass on caching, parallelism, and artifact reuse dropped builds to about 6 minutes. The remaining slow step is Synology DSM packaging, which I have not optimized yet. That change did not create adoption by itself. It shortened the maintainer loop so I could ship alternative install paths (Roon Extension Manager, QNAP and Synology packages, and early LMS plugin work) and keep up with user requests. The user benefit was simple: fewer hoops, faster installs, and fewer drop-offs.

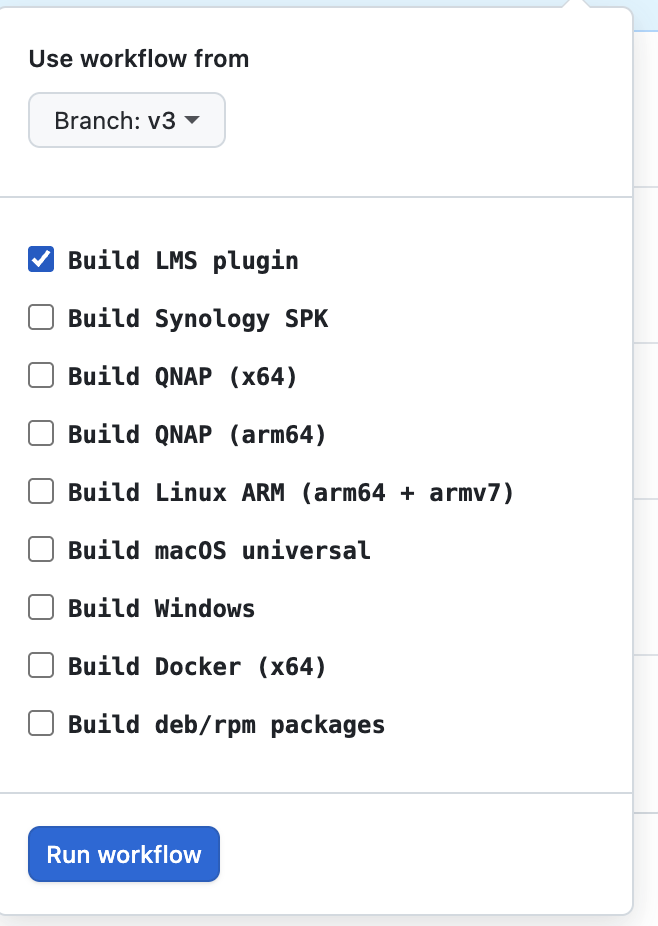

The next shift was treating packaging as product. I had separate workflows for PR builds and releases, which meant package issues only surfaced at release time. If I wanted to test a Synology SPK change, I had to merge and cut a release to find out if it worked. Unifying them into a single workflow with label-triggered builds means I can now add build:synology to a PR and test that specific package before merging.

Some distribution paths are harder. The LMS plugin downloads binaries at runtime from a manifest that points to release artifacts—artifacts that don’t exist until you release. The fix was bundling binaries directly into test packages so the full install flow can run without network access (PR #117). Packaging becomes iterable, not a release-day surprise. (See the appendix for the technical details.)

Patterns That Helped Across Both Contexts

Docker gripes in OSS are like SBOM scan failures in enterprise. They are feedback that the path from code to use is broken. People are not complaining for fun. They are pointing to where the system needs attention, and they feel it in the friction and unpredictability.

The common failure mode is unclear ownership. When the delivery path belongs to “everyone,” it belongs to no one, and the drag compounds quietly.

Quick test: who wakes up when installs break or scans flake, and do they have the mandate to fix the path instead of patching around it?

Ungoverned search creates thrash. Thrash hardens into bloat. Bloat turns the delivery path into a tax.

One approach that did not work well: burying delivery-path fixes inside feature work. Those changes kept getting deprioritized, ownership stayed fuzzy, and the wins were invisible because they did not show up in feature metrics. Pulling delivery-path work into its own track made the work visible and actually resourced.

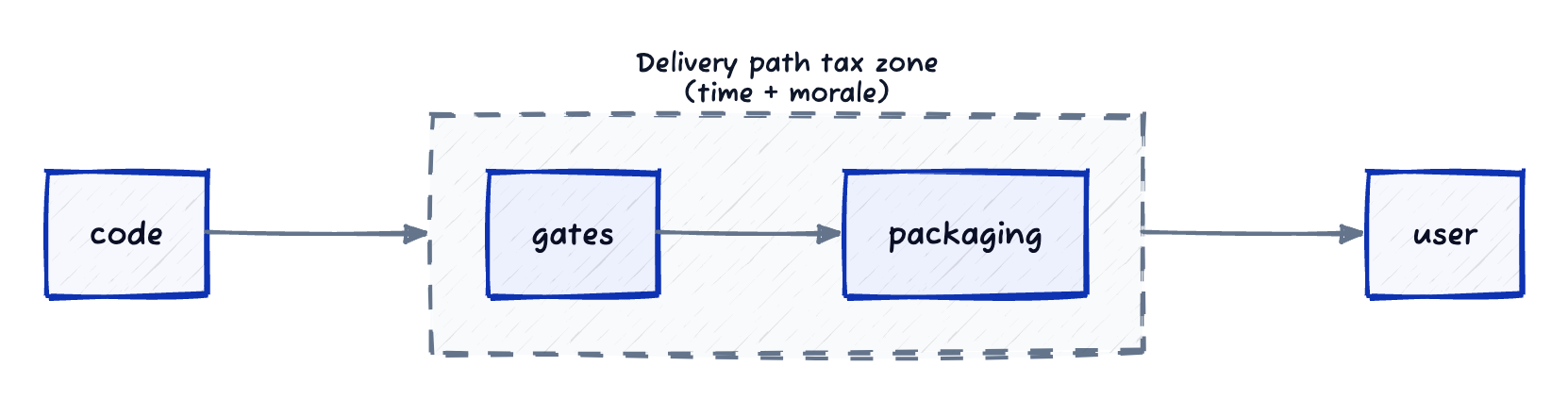

Figure: most friction lives between code and usable value.

The Core Thesis: The Delivery Path Is Your Product Surface

Whether you are solo on OSS or advising healthcare teams, it boils down to this: with real users, the delivery path is the entry point. A rough one means drop-offs, lost momentum, and wasted chances.

The key bottleneck is not making it. It is rolling it out steadily, broadly, and safely. That is a mix of tooling, governance, and release discipline. If you want velocity without thrash, invest where the constraint actually moved.

When execution is cheap, delivery is the work.

Delivery-path work is terraforming. You are reshaping the terrain so learning can happen by default.

If you are stuck in it, start with basics: map your last three releases and find where time actually went (code, review, or the gates after merge). That is your delivery-path tax. A simple template:

- Review-to-merge time

- Merge-to-prod time

- Gate/scan time (time spent blocked)

- Manual approvals count (or clicks)

Then measure cycle time, cache the obvious, and parallelize the easy wins.

Quick Glossary

- SBOM: Software bill of materials, a dependency inventory used in security scans.

- NAS: Network-attached storage; often the home of Synology or QNAP installs.

- DSM: Synology’s operating system and packaging format.

- LMS: Logitech Media Server.

Appendix: How the Build Workflow Actually Works

This is the technical detail behind the “40 minutes → 6 minutes” claim and the label-triggered packaging.

Philosophy: Single Source of Truth

One unified workflow (build.yml) instead of separate PR and release workflows. This prevents:

- Drift: Separate workflows diverge over time (different cache keys, different build steps)

- Duplication: Same job definitions copied between files

- Testing gaps: PR builds don’t match release builds

Configurable Builds via Labels

Add labels to your PR to enable optional builds:

| Label | Builds |

|---|---|

build:lms | LMS plugin ZIP |

build:synology | Synology SPK (x64 + arm64) |

build:qnap-arm | QNAP arm64 package |

build:linux-arm | Linux arm64 + armv7 binaries |

build:macos | macOS universal binary |

build:windows | Windows exe |

build:linux-packages | deb/rpm packages |

build:all | Everything |

PR builds: Nothing runs by default—add labels for exactly what you need to test.

Manual dispatch lets you test any combination of targets without cutting a release.

The Plan Job: Centralized Decision Logic

Instead of scattering build conditions across every job, a plan job runs first (~5 seconds) and computes what needs to be built. All downstream jobs simply check the plan outputs.

Benefits:

- Single source of truth: “What triggers ARM build?” is defined in ONE place

- Implicit dependency triggering:

build:synologylabel automatically enables ARM build - Easier debugging: The plan job summary shows exactly what will build

Caching Strategies

rust-cache + sccache together: They cache different things. sccache caches individual .o files keyed by source hash. rust-cache caches the target/ directory including proc-macro .dylib files that sccache cannot cache.

cargo-zigbuild for Linux cross-compilation: The cross tool runs cargo inside Docker containers, which breaks caching (container paths don’t match host paths). zigbuild uses Zig as a cross-linker without containers—rust-cache works normally.

Tool binary caching: Tools like dioxus-cli take 2-3 minutes to compile. Caching the binary (key: dx-cli-0.7.3) saves this on every run.

GHCR base images: GitHub Actions runners are co-located with GHCR (~10x faster pulls than Docker Hub, plus no rate limits).

Build Matrix

PRs: label what you need. Releases: everything runs automatically.

| Target | Caching | Build Tool | Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| Web Assets (WASM) | sccache + rust-cache | dx | build:web |

| Linux x86_64-musl | rust-cache | cargo-zigbuild | build:linux |

| Linux aarch64-musl | rust-cache | cargo-zigbuild | build:linux-arm |

| Linux armv7-musl | rust-cache | cargo-zigbuild | build:linux-arm |

| macOS universal | sccache + rust-cache | cargo + lipo | build:macos |

| Windows x86_64 | sccache + rust-cache | cargo | build:windows |

| Docker x64 | N/A | pre-built binary | build:docker |

| Synology SPK | N/A | tar | build:synology |

| QNAP x64 | N/A | qbuild (Docker) | build:qnap |

| QNAP arm64 | N/A | qbuild (Docker) | build:qnap-arm |

| Linux deb/rpm | N/A | fpm | build:linux-packages |

| LMS Plugin | N/A | zip | build:lms |

Lessons Learned

- Single workflow, conditional jobs: One

build.ymlprevents drift. Useif:conditions to control what runs. - Labels for PR customization: Use labels like

build:synologyto enable extra builds when testing specific platforms. - Avoid containerized cross-compilation:

crossbreaks caching.cargo-zigbuildcross-compiles without containers. - Universal macOS via lipo: Build each arch with native cargo, combine with

lipo. zigbuild can’t find macOS system frameworks. - QEMU for cross-arch testing: Smoke test armv7 binaries on x86_64 runners. Catches ABI issues before release.

- Build NAS packages directly: Synology’s toolkit downloads 1GB+ and creates unwanted debug packages. Build SPKs directly with

tar.

Comments powered by Disqus.