The Context Stack

How a constellation of tools creates the appearance of infinite memory

The Amnesia Problem

Every conversation with an AI assistant starts the same way: from zero. The model does not know what you built yesterday, does not remember the architectural decision you made last week, and has no idea why you chose that database or rejected that framework. You find yourself re-explaining context, re-establishing constraints, and re-teaching preferences.

This is not a bug in the models. It is a fundamental architectural constraint. Context windows are finite. Sessions end. State resets.

The standard workaround is documentation: READMEs, playbooks, meeting notes, checklists, and “how we do things” docs. But documentation is static, manual, and always incomplete. The moment you finish writing it, it starts drifting from reality. And it captures what you thought to write down, not the vast ocean of tacit knowledge that accumulates through actual work.

So we keep re-explaining. Every session. Every time.

The Insight

Here is the thing that changes everything once you see it:

Action is cheap. Knowing what to do is scarce.

AI agents can act. They can draft, plan, summarize, code, execute commands, create files, and operate in external tools. The scarce resource is not capability. It is knowing what to do. And knowing comes from context.

Think about your best collaborator. They are effective not because they type faster, but because they understand the codebase, the history, the constraints, the goals, and your preferences. They know what you meant when you said something ambiguous. They know what not to touch. They know why things are the way they are.

Once you have context, something else becomes possible:

With sufficient context, outcomes become more predictable before commitment.

This is the key shift. We are not trying to make AI omniscient. We are trying to make outcomes knowable enough before you commit resources. You should be able to ask “what happens if I do this?” and get a meaningful answer before the work is done.

That is not magic. That is context.

The Stack in 60 Seconds

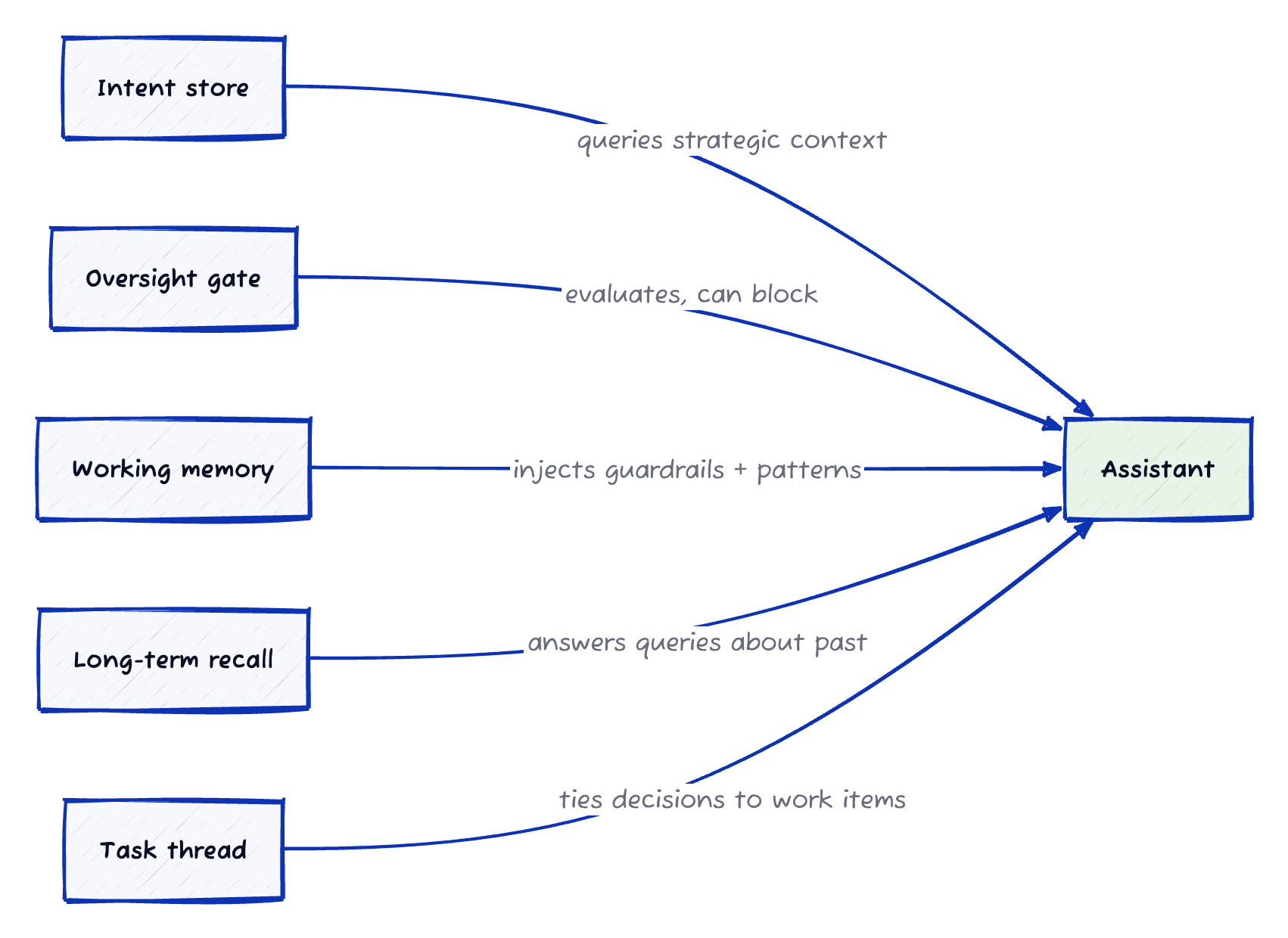

If you want an AI assistant to feel consistently useful, treat context as a stack. Each layer captures a different timescale:

- Strategic intent: what “good” means and why (months)

- Oversight: a check that stops drift before it becomes output (minutes)

- Working memory: distilled guardrails and patterns from recent work (days to weeks)

- Long-term recall: retrieval from older history with provenance (months to years)

- Task thread: an address that ties decisions and outcomes to a work item (always)

The layers do not need a monolith. They can compose via small artifacts and simple interfaces. They should also degrade gracefully when one layer is missing.

Memory Boundaries (What This Is and Isn’t)

When I say “memory”, I do not mean “the assistant remembers everything you ever said.” I mean a system that produces small, inspectable context artifacts: intent, constraints, decision logs, and distilled guardrails and patterns that were learned the hard way. The goal is not maximal retention. It is relevance at decision time.

Equally important: you should be able to see what context is being used, edit it, delete it, and decide what gets promoted from useful note to enforced constraint. Memory without governance is a liability.

Why a Stack?

If context is the bottleneck, we need systems that accumulate, structure, and surface it. But context operates at different timescales and abstraction levels:

- Strategic context changes over months: Why are we building this? What is the mission?

- Operational context changes over days: What did we learn last week? What patterns work here?

- Session context changes over minutes: What are we working on right now? What just happened?

A single monolithic tool cannot serve all these needs. You need a stack: layers that work together, each solving a different part of the problem at its natural timescale.

The tools described here are one concrete implementation of that idea. But the point of this post is the shape of the system: the layers, the interfaces, and the feedback loops. If you only adopt one layer, you still get value. If you adopt more, the value compounds.

They compose through simple interfaces (files, CLI calls, APIs), not tight integration. Each can work alone. Together, they create something greater.

Who is this for? Anyone using an LLM assistant who still feels weirdly ineffective: re-explaining the same background, repeating the same constraints, and watching good tools produce mediocre outcomes because they do not know your situation.

The Layers (Concept-First)

To keep this post lightweight, I will describe each layer by:

- What it’s for (the job)

- What it produces (the artifact)

- How it composes (the interface)

Two micro-examples will make this concrete:

- Shipping a risky change behind a feature flag

- Choosing a new tool for your team

Layer 1: Strategic Context (Intent)

Example moments:

- Feature flag rollout: “Success means shipping safely: reversible rollout, measurable impact, no surprises.”

- Team tool: “Success means reducing cycle time without adding admin burden. Adoption matters.”

Job: Keep “why” and “success” available at the moment of decision.

Artifact: A small, queryable hierarchy of intent: why → success criteria → constraints → tasks.

Interface: Query and logging. Any client can read intent and append decisions.

Layer 2: Metacognitive Oversight (Drift Detection and Stops)

Example moments:

- Feature flag rollout: You are polishing implementation details, but you still do not have a rollout plan, a kill switch, or a metric that defines “safe.”

- Team tool: You are deep in feature checklists and pricing tiers, but you have not defined a pilot or an exit plan.

An oversight layer surfaces a concern:

“You’re optimizing the wrong thing. Make the risk boundary (rollout and rollback) or adoption boundary (pilot and exit) explicit before you commit.”

The assistant sees this feedback in the current working context and must address the concern before proceeding.

In block mode, this is not a warning. It is a stop. The work does not continue until the concern is resolved (override, clarify intent, add constraints, or change approach). In advisory mode, it is guidance you can ignore. Both are useful. Block mode is for catastrophe boundaries and goal drift. Advisory mode is for taste and exploration.

Oversight monitors the conversation and evaluates the approach against checks like:

- Necessary? Real current problem, not hypothetical?

- Beyond the nearest peak? Alternatives explored?

- Sufficient? Could something simpler work?

- Fits the goal? On the critical path, or drifting?

Job: Catch “wrong kind of work” before it becomes irreversible output.

Artifact: Explicit concerns (or a clean bill of health) tied to the current work.

Interface: Evaluate the conversation and the work in progress, and optionally block on concerns.

Layer 3: Working Memory (Local Wisdom)

Example injections:

Guardrail: “No risky change ships without a feature flag and rollback plan.” Pattern: “Roll out 1% → 10% → 50% with monitoring. Write down the kill switch path.”

Guardrail: “No tool purchase without a time-boxed pilot and explicit exit criteria.” Pattern: “Run a two-week pilot with 3 real users. Measure onboarding friction. Decide quickly.”

You did not ask for this. You did not remember to write it down. But these guardrails are the difference between a smooth rollout and a Friday incident, and between a tool that gets adopted and one that becomes shelfware.

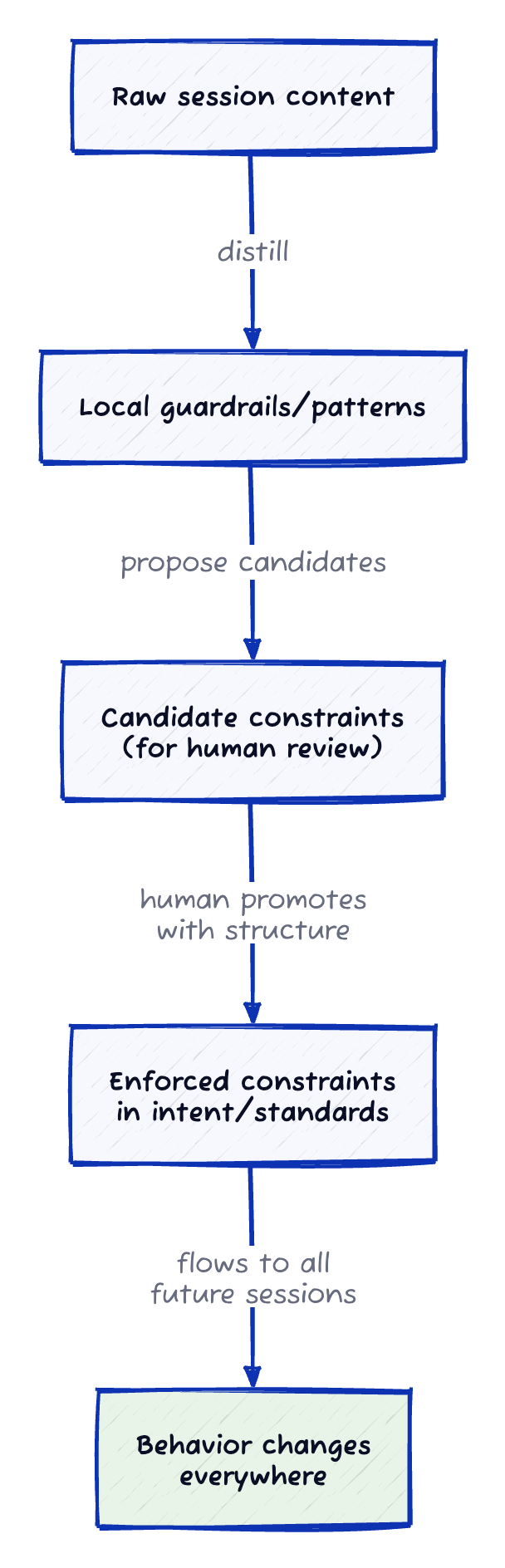

Job: Turn past work into small, reusable constraints and patterns.

Artifact: Two kinds of distilled memory:

- Guardrails (hard constraints)

- Patterns (practical advice that works here)

Interface: Batch distillation plus per-turn compilation (automatic context injection).

Some people call this metis: practical wisdom, the knowledge of how things work in practice rather than theory.

Layer 4: Persistent Memory (Long-Term Recall)

Working memory handles what you have learned here. But what about knowledge that spans months, teams, systems, and decisions?

Example queries:

- “What went wrong in our last rollout?” → surfaces: missing backfill step, no clear rollback owner.

- “Why did the last tool adoption fail?” → surfaces: training burden, no champion after week two.

Long-term recall should return provenance: where the learning came from and why it applies, not just an answer.

Job: Make “what did we learn before?” queryable across time and contexts.

Artifact: A graph of distilled knowledge with links (semantic and explicit).

Interface: Search plus related traversal (ideally via a simple API so any client can ask).

Task Thread (Work Identity)

Cutting through these layers is task tracking. Not as “project management,” but as identity. Work needs an address. It is the thread that ties everything together.

Naming the work gives everything an address:

- “Roll out billing refactor behind a flag”

- “Evaluate support tooling”

Then decisions (and their reasons) stop floating. They attach to the work that produced them.

Job: Ensure decisions and outcomes have an address (a task) rather than floating as trivia.

Artifact: Task identity plus lifecycle events (claimed, in-progress, finished).

Interface: Minimal CLI events that other layers can read.

How the Layers Compose

These layers do not share databases or runtime state. They compose through the oldest interface: text over pipes (simple pieces, loosely coupled, and gracefully degrading).

If one layer fails, the others continue. Recall does not need distillation to work. Oversight can still run without strategic intent. Each layer does its job. Together, they create emergent capability.

This is the Unix philosophy applied to AI infrastructure: small tools, clear interfaces, and graceful degradation. Tight integration looks elegant but creates brittleness.

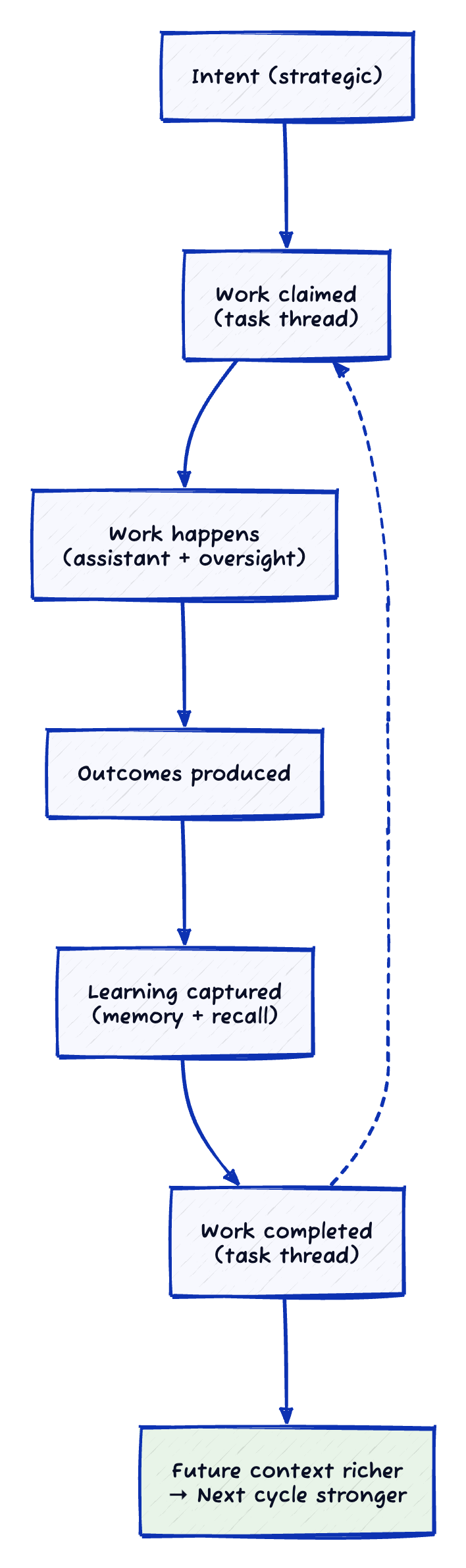

The Flywheel

What makes this a system rather than a collection of tools is the feedback loops.

Each cycle sharpens understanding. Strategy informs evaluation. Evaluation generates learning. Learning improves future work. Task tracking links it all to concrete work items.

There is also a promotion pathway for knowledge:

Learning becomes constraint only when it passes through human review. The AI surfaces candidates. Humans decide what becomes enforceable. Capture everything. Enforce selectively.

Getting Started (Without Going Tool-Heavy)

If you only adopt one idea from this post, adopt this: make context a first-class artifact.

If you only adopt one layer, adopt metacognitive oversight. It forces “are we doing the right thing?” back into the loop.

If you want the stack effect (compounding returns), the order that tends to work:

- Oversight (stops drift and catastrophe)

- Working memory (project guardrails and patterns)

- Task identity (give work an address)

- Strategic intent (align solutions with “why”)

- Long-term recall (query the long tail)

The implementation details can come later. The layer model stands on its own.

Day-One Quick Win (No History Required)

The cold start is real: you will not have “memory” on day one. But you can make the next turn better than the last turn immediately.

Create four tiny artifacts and keep them close to the work:

- Intent (1 paragraph): What are we doing and for whom? What does “good” look like?

- Constraints (a short list): Non-negotiables (security, time, budget, style).

- Current task (1 sentence): What are we trying to finish today?

- Decision log (bullets): Any irreversible choice plus why you chose it.

That is enough for an assistant (or a teammate, or future-you) to stop guessing. Once you have those, you can add the rest of the stack incrementally.

The Tradeoffs

Every system has costs. This one has several:

Token usage: Context injection means longer prompts. Memory and recall add material to turns. In practice, the cost can be modest (hundreds of tokens) and the value often exceeds it. Still, it is not free.

Latency: Oversight can add a round-trip evaluation step before certain operations. In “always” mode, this can add seconds. “Pull” mode (on-demand evaluation) trades safety for speed.

Complexity: More layers means more things that can break. The composition model helps (graceful degradation), but debugging “why didn’t that context appear?” requires understanding multiple systems.

Cold start: The stack needs data to be useful. Distillation needs past work. Recall needs history to search. Day one, you get less value than day thirty unless you deliberately create small context artifacts (intent, constraints, task, decision log) to seed the loop.

The bet is that context compounds, and that the investment pays increasing returns over time. Early experience suggests this is true, but your mileage depends on how much repeated work you do across sessions.

The Vision (North Star)

Where does this lead?

This is a north star: a direction, not a feature promise.

The goal is not to predict the future. It is to earn a useful forecast: a hypothesis about what will happen if you proceed, with a confidence band, the reasons behind it, and the most likely ways it goes wrong. This lets you refine intent or run a cheaper test before you commit.

The goal is a context substrate that makes outcomes more legible before commitment. It has two faces:

To the user: An entity with infinite context. You do not manage what it knows. You do not re-explain things. You do not bridge between sessions. It just knows.

Under the hood: A finite system creating the appearance of infinity through relevance. You do not need infinite storage. You need the right thing at the right time. The appearance of omniscience comes from never feeling the edges.

When you are about to spawn an agent on a task, the system can offer a forecast:

Forecast: A safe rollout plan for a risky change behind a feature flag: staged rollout, clear rollback path, and metrics that define “safe.” Confidence: Medium (depends on how observable the change is in production). Failure modes: rollout too fast, no true rollback path, missing backfill or migration step, no clear on-call owner. Next question: What is the rollback plan, and what metric triggers it?

You decide: commit, refine intent, add constraints, or try a different approach. The outcome becomes more knowable before the work begins.

That is the goal. Not better task management. Not fancier UX. A context substrate that makes the right thing to do obvious.

The stack exists today in partial form. Some layers are mature. Others are still being built. The full vision is a direction, not a destination.

Open Horizon Labs: The Implementation

For one concrete implementation of this stack, see Open Horizon Labs. Here’s how the conceptual layers map to tools:

| Layer | Tool | What it does |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic context | Open Horizons | Queryable hierarchy of intent: missions → aims → initiatives → tasks |

| Metacognitive oversight | superego | Evaluates work against constraints; can block on concerns |

| Working memory | wm | Distills guardrails and patterns; injects them per-turn |

| Long-term recall | (emerging) | Cross-context search with provenance |

| Task thread | ba | Gives work an address; tracks lifecycle events |

Bottle (bottle) is the installer that sets up these tools together and keeps them current.

The “Dive Pack” (a minimal context artifact: aim, constraints, known landmines, learnings, blocking question) is the entry ritual that seeds the loop before each session. For a practical example of this stack in action, see /posts/taming-the-chaos-dragon/.

That is the promise. That is the stack.

Written January 2026.

Comments powered by Disqus.